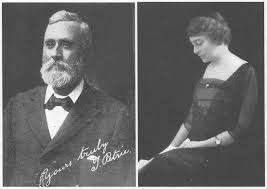

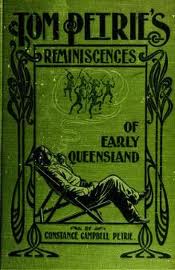

Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, written by his daughter Constance, provides detailed accounts of many aspects of Aboriginal culture and relates the experiences and adventures of Tom and his family from the 1830s to the 1860s. Reminiscences first appeared in serial form in the Queenslander from 26 April 1902 to 7 August 1903, though not in its entirety; it was published in book form in 1904. For a work that is extensively cited and recognised as an authority on Aboriginal and settler history in southeast Queensland, Reminiscences has attracted little critical analysis apart from Mark Cryle’s Introduction to the 1992 edition.

Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, written by his daughter Constance, provides detailed accounts of many aspects of Aboriginal culture and relates the experiences and adventures of Tom and his family from the 1830s to the 1860s. Reminiscences first appeared in serial form in the Queenslander from 26 April 1902 to 7 August 1903, though not in its entirety; it was published in book form in 1904. For a work that is extensively cited and recognised as an authority on Aboriginal and settler history in southeast Queensland, Reminiscences has attracted little critical analysis apart from Mark Cryle’s Introduction to the 1992 edition.

Reminiscences is a mix of several genres, including autobiography, biography, ethnology and anecdote, all of which rely on oral evidence. In 1905, A. G. Stevens called it “one of the most interesting and valuable books yet printed in Australia.” While it is an important historical document it contains elements of the colonial adventure romance. Reminiscences portrays a drama of the brave, enterprising settler/pioneer struggling to make a life for himself on a violent frontier. The story reinforces the positive image of a humanitarian, larrikin ancestor/colonist against the backdrop of a wild and savage land, perhaps satisfying the urge to recognise that which is best in ourselves in our “glorious” past.

Whether or not Reminiscences is accurate in every aspect, it has been accepted and lauded as an authentic account of life in early Brisbane. It was one of many memoirs of this type, written by squatters in their later years. W. H. Wilde and David Headon state in The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature that

the stream of memoirs and reminiscences continued undiminished in the second half of the nineteenth century. The writers, usually erstwhile squatters, government officials and public figures, reflected, often from heightened imagination of their twilight years, on the lively colonial times they had lived through.

According to Cryle, Reminiscences is important as a source because it is impartial and tells the past as Petrie saw it, and that “Petrie offers a rare glimpse—a ‘non-official’ perspective with no vested interest in reporting what ought to have happened. Rather it relates what did happen.” Perhaps one of the strongest declarations in Reminiscence’s favour was made by F. W. S. Cumbrae-Stewart in the Presidential Address he delivered at the Annual Meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland in 1918: “Mr Petrie’s book consists of two parts, the first of which relates to the blacks of Moreton Bay. On this subject it is the authority. No one knew more about the native inhabitant of this country than Thomas Petrie, or was on better terms with them.” As a historical source, Reminiscences is cited extensively in The Petrie Family: Building Colonial Brisbane (1992) by Dimity Dornan and Denis Cryle and appears in the Select Bibliography of The Commissariat Store (2001) by Tania Cleary and published by the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. However, it ranks no mention in historian Raymond Evans’ A History of Queensland (2007).

Constance’s inclusion of her own research, such as in the form of botanical names of plants, enhanced the perception of Reminiscences as being written in the scientific mode, thereby increasing its perceived authority and authenticity. An example of this appears on page 107 of Reminiscences: “Other dillies were made from bark-string, such as that of the ‘ngoa-nga’ (Moreton Bay fig-tree), the ‘braggain’ (Laportea sp.), the ‘nannam’ vine (Malaisia tortuosa), and the ‘cotton bush’ or ‘talwalpin’ (Hibiscus tiliaceus), found on the beach at Wynnum or elsewhere.”

Constance paints a picture of her father as a benevolent “master” or “brother” to the Turrbal who supposedly adored him, and he reveals himself to be a mischievous type who enjoyed sharing stories and jokes. Seen through Constance’s eyes, her father is a hero, an almost mythical personage she has constructed from the stories he had told her since her birth. To be sure, Constance was never going to write anything that would bring disrepute on her family; on the contrary, Reminiscences was written to reinforce the public image of the Petries, especially her father, as paragons of virtue and great pioneering heroes in Queensland’s history. Reminiscences is a collection of narratives, many of which were passed on to Tom by convicts, squatters and Aboriginal people.

Arguably the greatest acclaim for Tom Petrie and Reminiscences comes from Maroochy Barambah, Turrbal songwoman and law-woman, a direct descendant of Kulkarawa, whom Tom knew and mentions in the book. In her speech at the unveiling of the Tom Petrie Memorial in Petrie in 2010, she acknowledged the value of Tom’s accounts of the Turrbal people and his experience of them as “one of the most invaluable sources of information about life in the Moreton Bay penal colony.”

Beyond upholding the Petrie reputation, one of the principal reasons Tom and Constance wrote Reminiscences was to defend the Aboriginal people by providing justifications for their behaviour and to refute their portrayal as a treacherous and barbaric race. One example of this is when Constance presents a long dialogue between Dalaipi, the epitome of the “Noble Savage” who has refused the temptations offered by the whites, and Tom (182/83):

Before the whitefellow came,” Dalaipi said, “we wore no dress, but knew no shame, and were all free and happy; there was plenty to eat, and it was a pleasure to hunt for food. Then when the white man came among us, we were hunted from our ground, shot, poisoned, and had our daughters, sisters, and wives taken from us. Could you blame us if we killed the white man? If we had done likewise to them, would they not have murdered us?

Reminiscences was written at a time of a decline in fortune for Tom and his family due mainly to drought, and must have produced sorely-needed income. The book was the catalyst for the recognition Constance sought for her father and which came about when Governor William MacGregor unveiled a monument to honour Tom’s deeds in 1911, the year after his death. The ceremony was accompanied by the change of name of the community from North Pine to Petrie. Unfortunately, this decision sparked controversy and opposition from the local population for many years after the event and was one factor that ultimately led to Constance’s decline in health and her incarceration in the Goodna Asylum where she died in 1924, her father’s greatest defender.