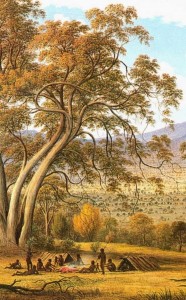

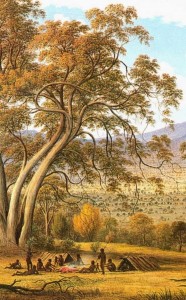

For the Australian Aboriginal people there is no separation between nature and humanity, as I explain in the Foreword to Turrwan. We construct our landscapes from a cultural perspective, they become a reflection of who we are as a society and how we have integrated with them over time. The white colonisers of Australia discovered a landscape sculpted in many areas by the Aboriginal inhabitants to make the country more productive. The Aboriginal people knew the land intimately; everything in their world has a story. In anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose’s words:

For the Australian Aboriginal people there is no separation between nature and humanity, as I explain in the Foreword to Turrwan. We construct our landscapes from a cultural perspective, they become a reflection of who we are as a society and how we have integrated with them over time. The white colonisers of Australia discovered a landscape sculpted in many areas by the Aboriginal inhabitants to make the country more productive. The Aboriginal people knew the land intimately; everything in their world has a story. In anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose’s words:

Here on this continent, there is no place where the feet of Aboriginal humanity have not preceded those of the settler. Nor is there any place where the country was not once fashioned and kept productive by Aboriginal people’s land management practices. There is no place without a history; there is no place that has not been imaginatively grasped through song, dance and design, no place where traditional owners cannot see the imprint of sacred creation.

In Turrwan I have attempted to provide some sense of this connection through, for example, the stories “The Beginning of Life” and “Mirrabooka,” and the kippa-making ceremony. Otherwise, my descriptions of the Brisbane area are the result of research and personal experience. I set out to capture some of the essence of Australia through descriptions of wildlife, flora and the weather, without overly resorting to metaphor as it is Tom telling the story and I did not want to make him over-poetic.

In my view, getting the setting right by producing a credible portrait of the environment and all that existed in the area at the time in question is crucial for a work of historical fiction, so writing a novel set in the region where you live has distinct advantages. I have lived on the banks of Cedar Creek, 30 km to the north-west of Brisbane city centre, for the last 17 years and have come to know the landscape, climate, flora and fauna of the region well. Although I first visited Brisbane more than 40 years ago—I was born and raised on the Atherton Tablelands in North Queensland and also lived and worked in Central Queensland as a teenager—it has only been in recent times that I have become familiar with its geography and history. The fact that I have extensively explored the city and surrounds on foot, by car, bus, train and boat has helped me recreate the terrain as it once must have been before the steel and glass structures that now dominate the skyline came into being.

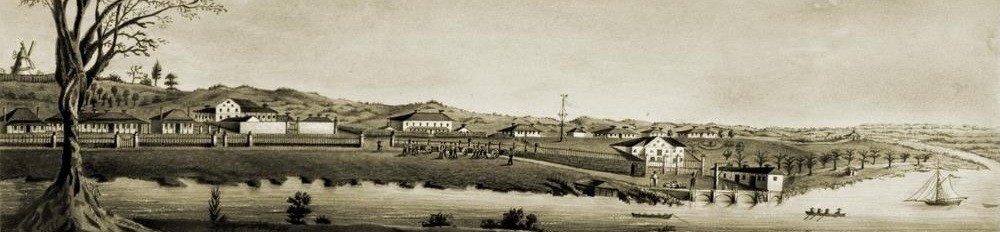

Old maps, drawings, photographs and descriptions were invaluable in helping me create a picture in my mind of the area as it was nearly 200 years ago, while modern technology in the form of Google Earth also helped. The old windmill on the hill at Wickham Terrace and the commissariat store snuggled into the riverbank on Queen’s Wharf Rd are all that are left from those early times and served as critical landmarks in my understanding of the layout of Brisbane and as indicators allowing me to imagine how the area once looked. When I visited the windmill I was reminded of a passage in Kate Grenville’s Searching for the Secret River (2006) when she was in London tracing her relative Wiseman’s path: “I laid the palm of my hand on the rough limestone, feeling the cold grit on my skin. His hand might have lain there too, leaving molecules behind, wedged in the grain of the stone, as he leaned on it talking to someone, or . . . what?” (50). I touched the smooth, conical wall of the mill and imagined the machinery grinding noisily in its interior as the convicts sweated and slaved on the treadmill in the sweltering heat under the watchful eye of the soldiers. Perhaps Tom had once placed his hand in exactly the same spot.

Further afield, at the bora ring near Samford (one of the best preserved in the region), I trudged along the ridge line following the sacred path between the large and small rings, trying to create an image in my mind of the kippa ceremony and to capture a sense of the occasion. To further cement my understanding of the terrain I drew a rough sketch showing the creeks, the boys’ huts, the bora rings and the kakka. Tom would also have trodden this way.

Further afield, at the bora ring near Samford (one of the best preserved in the region), I trudged along the ridge line following the sacred path between the large and small rings, trying to create an image in my mind of the kippa ceremony and to capture a sense of the occasion. To further cement my understanding of the terrain I drew a rough sketch showing the creeks, the boys’ huts, the bora rings and the kakka. Tom would also have trodden this way.

Unfortunately, the old Murrumba Homestead at Petrie (a 20 minute drive from where I live) was demolished and has been replaced with a school. However, I did find a number of photos, and many of the trees Tom planted still stand on the hillside overlooking the town of Petrie and the North Pine River.

Murrumba

For the Australian Aboriginal people there is no separation between nature and humanity, as I explain in the Foreword to Turrwan. We construct our landscapes from a cultural perspective, they become a reflection of who we are as a society and how we have integrated with them over time. The white colonisers of Australia discovered a landscape sculpted in many areas by the Aboriginal inhabitants to make the country more productive. The Aboriginal people knew the land intimately; everything in their world has a story. In anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose’s words:

For the Australian Aboriginal people there is no separation between nature and humanity, as I explain in the Foreword to Turrwan. We construct our landscapes from a cultural perspective, they become a reflection of who we are as a society and how we have integrated with them over time. The white colonisers of Australia discovered a landscape sculpted in many areas by the Aboriginal inhabitants to make the country more productive. The Aboriginal people knew the land intimately; everything in their world has a story. In anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose’s words: