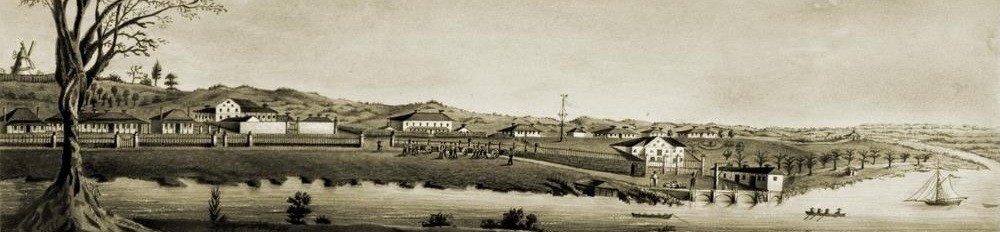

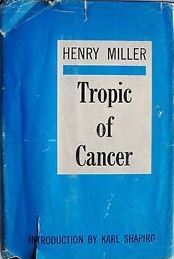

I find it fascinating that the two top-ranked white men who, in 1824, established the first settlement at Red Cliff Point in what would become Queensland, bear the names of literary giants. Commandant Henry Miller evokes the American novelist who shocked the world with Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn in the 1930s. The sexually explicit novels were banned for thirty years in the United States. Miller’s work was dubbed “fictionalised autobiography” as much of the content reflects the author’s life. Surgeon/storekeeper Walter Scott, second-in-command at Red Cliff, lived at the same time as his namesake who became famous for his poetry then his novels such as Waverley and Ivanhoe. This reminded me of the following article about the origins of the historical novel, which I wrote for my PhD thesis but did not use; I talk about Scott here towards the end.

I find it fascinating that the two top-ranked white men who, in 1824, established the first settlement at Red Cliff Point in what would become Queensland, bear the names of literary giants. Commandant Henry Miller evokes the American novelist who shocked the world with Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn in the 1930s. The sexually explicit novels were banned for thirty years in the United States. Miller’s work was dubbed “fictionalised autobiography” as much of the content reflects the author’s life. Surgeon/storekeeper Walter Scott, second-in-command at Red Cliff, lived at the same time as his namesake who became famous for his poetry then his novels such as Waverley and Ivanhoe. This reminded me of the following article about the origins of the historical novel, which I wrote for my PhD thesis but did not use; I talk about Scott here towards the end.

Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey (eighth century BC) were the first written narratives in Western culture and marked the transition from the oral epic to literary forms from which would ultimately stem the novel. In these works, fact and fiction blend in a marriage of history and myth passed on down through the ages. From these common beginnings factual and fictional writing emerged into separate forms before eventually coming together again in the novel.

Factual and fictional writing began going their separate ways in the fifth century BC with Herodotus’s account of the Greco-Persian wars in The Histories. The separation is complete with the empirical writings of Thucydides whose rationalism was not to be equalled until the seventeenth century. The fourth century BC was critical in the development of the historical novel. In his Cyropedia, historian Xenophon mixes fact and fiction in his depiction of Cyrus the Great, a historical figure.

Some scholars argue that Roman literary theory put a deliberate end to the development of the historical narrative as a form of literature. Empiricists insisted on facts and objectivity to the detriment of a narrative based in reality; as a result historical writing became a dry affair with little attraction for the lay person. However, fiction continued to develop in the form of the Greek romance. Marked by a highly stylised plot and little attention to history, the romance became popular throughout the Mediterranean region, and later had a significant influence on the development of the novel.

The dominant literary texts throughout the Middle Ages were religious while secular writers concentrated on poetry, drama and especially allegory. It suffices here to mention such important works as the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, the French classic La Chanson de Roland and the Icelandic family sagas among many others. The thirteenth century Icelandic sagas are important because they are a marriage of history and romance and therefore a precursor to the novel.

A work that did have a significant impact on the later development of the historical novel in Europe was Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605). The story is about a deluded landowner who sets out as a knight on a quest to rescue a maiden in distress. In his insanity, Don Quixote sees windmills as attacking knights and a donkey as a warhorse. Perhaps most importantly, Don Quixote popularised prose writing from which the novel subsequently evolved.

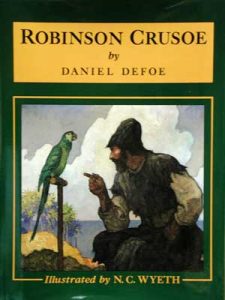

The first En glish novels, for example Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Moll Flanders (1722), differed from the allegory or romance by accentuating realism and the development of character in a social context. The latter half of the eighteenth century saw the emergence of the Gothic novel which is often set in the Middle Ages and deals with horror, mystery and terror in a dark form of historical fiction. One example is Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, often considered to be the first of the genre; the novel is presented as a translation of ancient texts, a real archival document in its own right. The aim of the Gothic novel is to use our preconceptions of what was supposedly a terrifying era as the stage on which indescribable horrors can manifest to terrorise our modern sensitivities.

glish novels, for example Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Moll Flanders (1722), differed from the allegory or romance by accentuating realism and the development of character in a social context. The latter half of the eighteenth century saw the emergence of the Gothic novel which is often set in the Middle Ages and deals with horror, mystery and terror in a dark form of historical fiction. One example is Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, often considered to be the first of the genre; the novel is presented as a translation of ancient texts, a real archival document in its own right. The aim of the Gothic novel is to use our preconceptions of what was supposedly a terrifying era as the stage on which indescribable horrors can manifest to terrorise our modern sensitivities.

The historical novel had its origins in ancient times and continued to develop through the ages, but it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that it became established as a popular genre. Most critics regard Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley (published anonymous ly in 1814) as the earliest example of the historical novel, to a large part due to its widespread popularity and ensuing influence on the novel form. This work of fiction was based on in-depth research that Scott included as notes covering ballads, poetry, culture, politics, historical events and more.

ly in 1814) as the earliest example of the historical novel, to a large part due to its widespread popularity and ensuing influence on the novel form. This work of fiction was based on in-depth research that Scott included as notes covering ballads, poetry, culture, politics, historical events and more.

Andrew Hook, in the introduction to the 1972 edition of Waverley, claims the book and later works by Scott played a crucial role in establishing the novel as the predominant form of Western narrative literature for the last 200 years. Scott’s novels had an unprecedented influence on Western readers that has not been seen since. Driven by a renewed interest in the customs, characters and cultures of the past and new technology in printing, the public consumed Scott’s historical fiction with a fervour hard to imagine in today’s society. Hook argues that Scott’s work saw the birth of the historical novel as a new literary genre which rapidly claimed a place as one of the most popular forms of the novel.

Waverley’s perceived authenticity and writing style revolutionised the novel’s image, gaining it much authority and reputation. Waverley also had a significant influence on the way the world saw Scotland. Scott’s depiction of Scotland’s history, its culture and people, inflamed the imagination of his readers to the point that it became increasingly recognised as a land of romance and adventure.