Many writers fled Brisbane during the Joh Bjelke-Petersen era (1968–87). Queensland has been represented in the past as a cultureless backwater inhabited by rednecks. The state was perceived as being of no interest, a rural backward society caught between its violent frontier past and an artificial present. However, this negative image, while still valid for some, has changed radically since the World Expo in 1988 and the demise of Bjelke-Petersen. By the end of the twentieth century Brisbane had begun to reposition itself as a cosmopolitan city with a healthy cultural base.

Many writers fled Brisbane during the Joh Bjelke-Petersen era (1968–87). Queensland has been represented in the past as a cultureless backwater inhabited by rednecks. The state was perceived as being of no interest, a rural backward society caught between its violent frontier past and an artificial present. However, this negative image, while still valid for some, has changed radically since the World Expo in 1988 and the demise of Bjelke-Petersen. By the end of the twentieth century Brisbane had begun to reposition itself as a cosmopolitan city with a healthy cultural base.

A number of factors have also contributed to this transformation. The population has increased through migration, Queensland’s image as a tourist destination has been enhanced through sophisticated marketing and the government has invested in cultural organisations and practitioners. At the same time, Queensland writers such as Venero Armmano, John Birmingham, Nick Earls, Andrew McGahan and Simon Cleary among many others have played a central role in changing how Brisbane is perceived. For McGahan, the city is far from ugly. In his novel, 1988, he describes his return after a stint in the north:

The glow in the sky. Orange streetlights. Outlying suburbs. It was beautiful. The highway turned onto the six-lane arterial. We came in through Oxley and Annerly, flowing with the traffic. Then the city highrises were in view, alight, multi-coloured. Brisbane. It was impossibly beautiful.

The negative qualities of Brisbane, as portrayed by writers like Malouf in Johhno, have  been refigured by other writers, and Malouf himself, so as to portray Brisbane in a positive way. One transformation in particular was how the old wooden houses became to represent all that was good about the city. The “Queenslander,” as the house is known, was epitomised in Malouf’s 12 Edmonstone Street (1985), where he describes the building as “a one-storeyed weatherboard, a style of house so common then as to be quite unremarkable; Brisbane was a one-storeyed weatherboard town”.

been refigured by other writers, and Malouf himself, so as to portray Brisbane in a positive way. One transformation in particular was how the old wooden houses became to represent all that was good about the city. The “Queenslander,” as the house is known, was epitomised in Malouf’s 12 Edmonstone Street (1985), where he describes the building as “a one-storeyed weatherboard, a style of house so common then as to be quite unremarkable; Brisbane was a one-storeyed weatherboard town”.

Contemporary writers may be reconfiguring Brisbane in a positive manner, but the question still remains of why so few historical novels have been written about the colonial era in Brisbane. Is it due to a collective will to forget the early history of Queensland, especially the “birthstain” of the penal colony and the desire of emancipists and their descendants to hide their convict origins? This denial of our convict past was deepened by a desire to forget the way early settlers treated the Aboriginal people—the massacres, the poisonings, the diseases. The frontier violence in Queensland has been replaced by the notion of the brave pioneer taming a wild country and has been collectively forgotten in the same way as our convict past has. Australians are unwilling to treat with this period because they would need to look deep within themselves and confront the demons that are unleashed when one people dispossesses another.

Even so, since the 1970s, more and more family historians have been searching the archives and discovering convicts in the family tree. Now people are accepting their convict ancestry to the point that it has become a badge of honour for some. We are also beginning to recognise and acknowledge the suffering the whites caused in their early interactions with the Indigenous people of Australia. Then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s “Apology to the Stolen Generations” in 2008 is one example.

And has literature itself unwittingly played a role in putting novelists off? Indeed, as we have seen, a thread of negative images of the city runs through the novels discussed in earlier articles, from The Curse in 1894, which depicts a city in decay, to the myth of the hostile country portr ayed in Penton’s Landtakers and then the city concealing its past in the follow-up Inheritors. The line continues through the works of Malouf: Johnno, Anderson: Tirra Lira and Astley: Reading, who paint Brisbane as uninteresting, a place to flee from. Does this sense of Brisbane as not worthy of attention still haunt the collective subconscious and reinforce the desire to forget the city’s past? Nick Earls, author of Zigzag Street (1996), which is set in Brisbane, says that, “[f]or years I wrote things and deliberately avoided setting them in South-East Queensland because people didn’t seem to do that and the area didn’t seem to be regarded as worthy of carrying a story.”

ayed in Penton’s Landtakers and then the city concealing its past in the follow-up Inheritors. The line continues through the works of Malouf: Johnno, Anderson: Tirra Lira and Astley: Reading, who paint Brisbane as uninteresting, a place to flee from. Does this sense of Brisbane as not worthy of attention still haunt the collective subconscious and reinforce the desire to forget the city’s past? Nick Earls, author of Zigzag Street (1996), which is set in Brisbane, says that, “[f]or years I wrote things and deliberately avoided setting them in South-East Queensland because people didn’t seem to do that and the area didn’t seem to be regarded as worthy of carrying a story.”

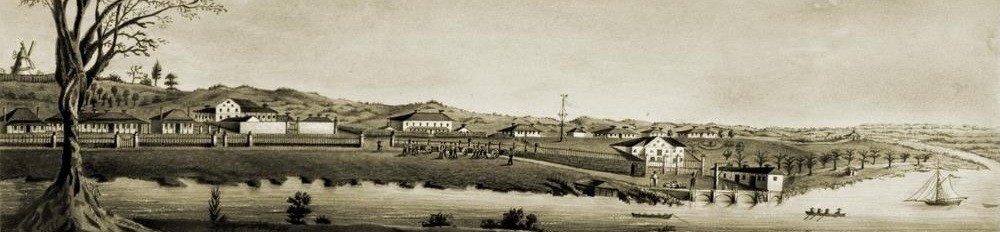

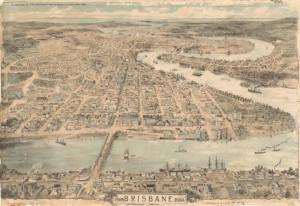

And so our writers escape from Brisbane to look elsewhere for their stories. Two contemporary historical novelists who have lived in or around Brisbane have turned towards the “old country” to tell their tales. Kate Morton has chosen to set her novels in England, flitting back and forth from the present to the first half of the twentieth century, beginning with The House at Riverton/The Shifting Fog (2006) through to The Secret Keeper (2012). M. K. Hume, who grew up in Ipswich, is consumed by ancient history which, as she says on her website, she “loved to teach . . . using stories to bring the ancient world to life for my students.” Hume has written two trilogies centred on her “first love, King Arthur, and the legends of the Arthuriad.” It seems the wonders of our distant ancestors in Europe are more attractive to writers than what happened in Brisbane in its early days. That is quite understandable, but more and more people want to learn about Brisbane’s past. However, only time will tell whether or not historical novelists turn their eye to the colonial era and do justice to the city. Brisbane has changed much since those far-off days of a tiny settlement tucked into a bend in the river and ringed with an endless sea of vegetation and later its image as a cultureless backwater where nothing ever happened. Now the city has begun to embrace its past more than ever and has become a place to move to, not to escape from.

The overall survey shows a common thread in the early writings from Praed through to Penton. Whiteness is either questioned or affirmed, while inter-racial relations on the frontier and in the city explored. A number of these works, White or Yellow? in particular, raise questions of national identity. Another thread links novels written in more recent times, from Malouf to Cleary. In these works, the built environment features along with the landscape and Brisbane takes on character as a place in the hearts and minds of its inhabitants. Anderson and Shaw represent yet another strand of novelists (to which I belong), whose “settler accounts,” like Penton, take place in colonial times and explore various aspects of the period. What stands out in many of these works is the way the river is depicted as defining the city, an essential part of its character.

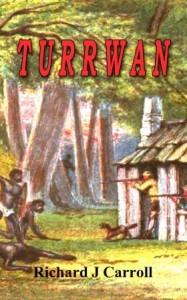

Turrwan has little in common with some of the early works set in Brisbane, especially  White or Yellow? and The Curse. However, like many of the works cited in this analysis, Turrwan explores relationships between Black and White on Queensland’s frontier. In contrast, Anderson’s The Commandant makes little reference to the Aboriginal people except as a vague presence until the murder of Logan. Yet, there is a similarity between my work and Anderson’s in that we both use fictive characters who confront well-known historical figures. Despite the fictional content, I, like Anderson, have strived to respect the historical record. Barry states that in The Commandant, “[t]here is great authenticity in the factual background of the novel.” However, as we saw earlier, Penton was wrong with the dates in Landtakers, and as shown earlier, Shaw was inaccurate with historical details in Mango Hill. These may simply have been details overlooked by the authors, but it does reflect negatively on the historical veracity of the works.

White or Yellow? and The Curse. However, like many of the works cited in this analysis, Turrwan explores relationships between Black and White on Queensland’s frontier. In contrast, Anderson’s The Commandant makes little reference to the Aboriginal people except as a vague presence until the murder of Logan. Yet, there is a similarity between my work and Anderson’s in that we both use fictive characters who confront well-known historical figures. Despite the fictional content, I, like Anderson, have strived to respect the historical record. Barry states that in The Commandant, “[t]here is great authenticity in the factual background of the novel.” However, as we saw earlier, Penton was wrong with the dates in Landtakers, and as shown earlier, Shaw was inaccurate with historical details in Mango Hill. These may simply have been details overlooked by the authors, but it does reflect negatively on the historical veracity of the works.

From the foregoing, it is clear that Australian fiction writers have neglected the early history of Brisbane and that my novel could help fill this gap. No historical novels have been set entirely in Brisbane and its surrounds in the period covered in Turrwan, that is, from 1830 to 1862.

So novelists, to your pens.