I awoke at 6.30 am to the piercing shrill of my alarm clock and dragged myself out of bed. It was mid-December and the sun was already well into the sky and promising another scorcher. This was my first day of work in my first real job. I had just finished Grade 12 at the Emerald High school in Central Queensland where I had been named Senior Dux – not such a great feat as there were only eleven in the class.

My step-father Bill worked for the Irrigation and Water Supply Commission (IWSC) and was the storekeeper during the construction of Fairbairn Dam on the Nogoa River about twenty kilometres southwest of Emerald. He had managed to get me a job as a labourer. At sixteen, I was 178 cm, skinny as a rake and wore thick black plastic-framed glasses. Not exactly Arnold Schwarzenegger.

My step-father Bill worked for the Irrigation and Water Supply Commission (IWSC) and was the storekeeper during the construction of Fairbairn Dam on the Nogoa River about twenty kilometres southwest of Emerald. He had managed to get me a job as a labourer. At sixteen, I was 178 cm, skinny as a rake and wore thick black plastic-framed glasses. Not exactly Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The first day I was set to work on a compacting machine that vibrated and bounced up and down like a frenzied robot out of control. I was supposed to hold it and direct it along the bank of a small coffer dam. I think I actually bounced more than the bloody machine! At the close of the day my arms felt like they had been wrenched out of their sockets. I was totally exhausted and collapsed gratefully into my bed straight after tea.

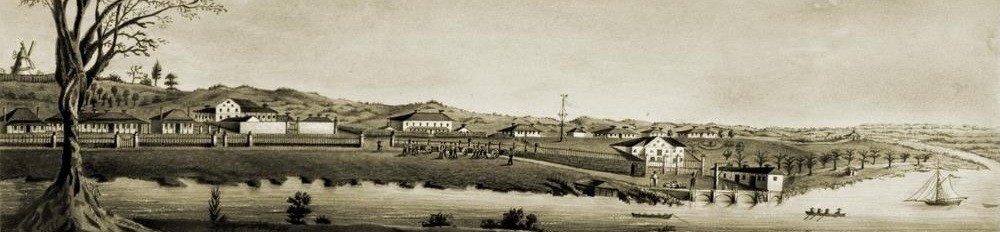

Fairbairn Dam was being built to provide water to irrigate the rich black soil plains around Emerald. The small township built especially to house the workforce consisted of several distinct sections. The lowest of these was the quarters for the single men, row upon row of barracks, the great mess hall, and the shower and ablutions block. Next were the two-bedroomed huts for the married men, three-bedroomed huts for the married “staff” workers and a little further up the hill were the barracks for the single “staff.” Right up on top of “snob hill” were proper houses reserved for senior staff such as engineers and supervisors.

On my second day of work the foreman took pity on me and put me with a gang digging trenches for water pipes to feed a new section of huts. I swung a pick and heaved on a shovel until my hands were red and blistered. But worse was to come. For some unknown reason I found myself one day on the steep rocky slope of the proposed spillway, a huge jackhammer, that weighed about as much as I did, in my hands. The shaly rock had to be cut back to the required angle and this was the only way to do it. Since then I have done a large variety of jobs but this was by far the worst. I couldn’t get to sleep that night as it felt as though I was still on the spillway, my whole body and especially my hands still vibrating to the rhythm of the hammer.

The dam wall was to be made from compacted clay and would stretch across the river between two high points. A vast area across the valley floor had been cleared of timber, which bulldozers had pushed into massive pyramids. I was handed a box of matches – my job: set fire to these stacks and pick up all the scattered bits of wood missed by the dozers. I thought I had landed in hell as the fires blazed. The usual temperature of forty degrees Celsius was cool to what I experienced that day.

Then I got lucky. I was assigned to look after the filtration plant that supplied water to the township. The small fenced complex sat on the top of a hill well above the houses. Muddy brown water was pumped from the river far below to a square tank on a tower. From there it passed into two conical shaped flocculation tanks where alum was used to settle the silt out of the water, after which lime was added to rectify the ph and finally chlorine was added to kill any germs. The water was then stored in an enormous block of a tank before being distributed to the town. My job was to ensure the right mix of chemicals went where they were supposed to and to make sure everything worked correctly. It was a cushy job and I had time some days to sit reading a book and smoking my pipe in the cool shade under the flocculation tanks.

When I turned seventeen in January and got my driver’s license I was given a ute to drive to work, an arrangement that was soon cancelled when I turned too sharply into the complex and the steel fence post scored jagged gashes along the left side of the ute. With head bowed, I showed it to Karl Moser, the German foreman, who exploded. “Vot haf you done to my car? Bloody hell!” Needless to say, I had to walk up the steep hill to work after that.

In the few weeks I was guardian of the water there was only one other real disaster. One day I forgot to turn the pump from the river off – it was automatic normally – I don’t know what happened but river water was coming up and no chemicals were going into the system. When the people in their houses turned on their taps, a thick brown undrinkable mess poured forth. I kept a low profile until the dust had settled, literally.