The first half of the twentieth century saw few novels written about Brisbane, or even Queensland. Three historical novels stand out in this period. The Romance of Runnibede by Steele Rudd aka Arthur Davis was published in 1927. Set on the Darling Downs in the mid-nineteenth century, the book narrates the lives of squatters and the Aboriginal resistance to the white presence, but there is no mention of Brisbane. Brian Penton’s Landtakers, the Story of an Epoch, published in 1934, also explores squatter life and the treatment of the Aboriginal people from the 1840s to the 1860s. Landtakers relates the life of Derek Cabell, a young English immigrant who arrives in Moreton Bay in 1844. Penton describes Brisbane:

The first half of the twentieth century saw few novels written about Brisbane, or even Queensland. Three historical novels stand out in this period. The Romance of Runnibede by Steele Rudd aka Arthur Davis was published in 1927. Set on the Darling Downs in the mid-nineteenth century, the book narrates the lives of squatters and the Aboriginal resistance to the white presence, but there is no mention of Brisbane. Brian Penton’s Landtakers, the Story of an Epoch, published in 1934, also explores squatter life and the treatment of the Aboriginal people from the 1840s to the 1860s. Landtakers relates the life of Derek Cabell, a young English immigrant who arrives in Moreton Bay in 1844. Penton describes Brisbane:

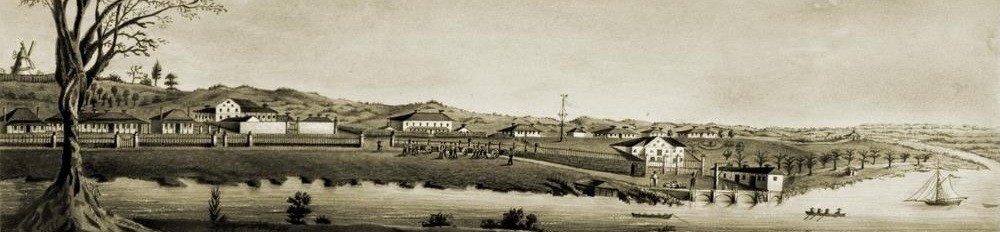

Red earth and blue sky met in the jagged line of a near horizon. In the middle of this vault stood the settlement—a prison within a prison. Shanties built of black bark twisted by the fierce sun, with crazy-shaped doors and glassless windows. Jail and barracks of stone. A yellow stone windmill. A long, dusty, empty street. Sheep, a few cows, pigs, wide patches of yellow Indian corn. At one side of the valley a river shimmered in the sunlight; at each end of the valley the bush. Into illimitable blue distance it faded, across unexplored mountains and plains, grey, motionless and silent.

Here Penton evokes a sense of isolation in a vaguely intimidating landscape from which there is no escape from the “prison within a prison.”

Penton has played with history, as he describes convicts in chains and other aspects of the penal settlement. However, Brisbane was no longer a penal institution in 1844 as the prison was closed down in 1842. Only the first chapter of Landtakers is set in Brisbane, where Cabell’s anger at the loss of some sheep boils over in a bar. His opinion of the land was echoed by many of the first settlers: “’I hate it,’ he said pathetically. ‘I loathe it. It’s so different from England, this eternal, cursed, colourless bush.’” Perhaps this myth of a hostile country is also partly responsible for later depictions in literature of the inhabitants of Brisbane, like Praed, wanting to escape to a better life in Europe.

In Landtakers, Cabell is bitter about his situation and prospects for the future, and blames the land for his failures. Two years after his arrival, he drives a mob of sheep and cattle 600 kilometres northwest of Brisbane where he establishes a huge holding. Over the years, Cabell commits atrocities including the massacre of Aboriginal people. Landtakers provides an unabridged view of life on the Queensland frontier and an image of the pioneer as an anti-hero. The role that landscape plays in shaping how we perceive a work cannot be underestimated. Landtakers, in the words of David Carter,

shows a landscape that is almost gothic, that sometimes seems positively malevolent in its own right not merely the scene for malevolent human action. Imagining Queensland as a place of gothic haunting, guilty secrets, sexual repression, and violence—the other side of paradise—is a surprisingly strong theme in literature.

Inheritors (1936), the sequel to Landtakers, evokes this idea of guilt and suppression as it takes aim at the political corruption in Queensland and portrays Brisbane towards the end of the nineteenth century as being obsessed with hiding its not so glorious past of deceit and lies.

It was not until the mid-twentieth century and Vance Palmer’s Golconda (1948), the first of  a trilogy partially set in Brisbane that some form of continuity in using the city as a setting developed. The three novels, including Seedtime (1957) and The Big Fellow (1959), are loosely based on the life of Ted Theodore, a Queensland politician, and span the period from the late 1920s to the 1950s. The main protagonist, Macy Donovan, starts out as a union organiser in the new mining town of Golconda in outback Queensland and later rises to become premier of the state. It is not until Seedtime that Palmer gives life to Brisbane with some parts being shown in more detail. In the following passage from Seedtime, Donovan has just left hospital after recovering from a knifing:

a trilogy partially set in Brisbane that some form of continuity in using the city as a setting developed. The three novels, including Seedtime (1957) and The Big Fellow (1959), are loosely based on the life of Ted Theodore, a Queensland politician, and span the period from the late 1920s to the 1950s. The main protagonist, Macy Donovan, starts out as a union organiser in the new mining town of Golconda in outback Queensland and later rises to become premier of the state. It is not until Seedtime that Palmer gives life to Brisbane with some parts being shown in more detail. In the following passage from Seedtime, Donovan has just left hospital after recovering from a knifing:

A sense of exultation was making Donovan feel light-headed as he left the hospital behind him and sauntered down towards the North Quay. Morning showers had washed the streets clean and a cool, bright wind was moving in from the Bay; there was even the tang of the sea in it. Winding through the massed spread of buildings in the city below, the river showed in streaks of silver and where it widened into a broad reach along the Quay the dark blobs of small cargo-boats could be seen like moving water-beetles through the bamboos of the Esplanade.

Here Palmer uses the rain, the smell of the sea, and the river to evoke a sense of well-being in the city.

In the next instalment, I look at David Malouf’s Johnno and Jessica Anderson’s The Commandant, amongst others, continuing the theme of Brisbane as a place to escape from.