Lionel Shriver’s speech at the Brisbane Writer’s Festival about appropriation and the ensuing reactions prompted me to dust off “White Writing Black” a major chapter in my PhD thesis. Here I present a revised edition of the first section and will follow with more later.

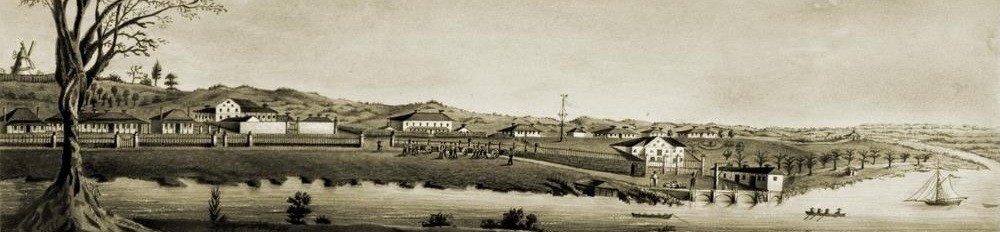

The non-Indigenous writer creating stories set in Australia faces a dilemma: whether or not to write about the Aboriginal people and their culture, and if so, how. In the words of José Borghino, policy director at International Publishers Association, “the politics of speaking in an Aboriginal voice, if you’re not Aboriginal, is at best fraught and at worst a nightmare.” However, to write a novel set in early Brisbane, as mine is, with little mention of the original inhabitants would be to provide a false impression, an inauthentic portrayal of the true situation and to perpetuate the myth of terra nullius. Yet, as a white person, if I include Aboriginal characters, I need to be aware of the complexities involved in speaking for and about their experiences.

The non-Indigenous writer creating stories set in Australia faces a dilemma: whether or not to write about the Aboriginal people and their culture, and if so, how. In the words of José Borghino, policy director at International Publishers Association, “the politics of speaking in an Aboriginal voice, if you’re not Aboriginal, is at best fraught and at worst a nightmare.” However, to write a novel set in early Brisbane, as mine is, with little mention of the original inhabitants would be to provide a false impression, an inauthentic portrayal of the true situation and to perpetuate the myth of terra nullius. Yet, as a white person, if I include Aboriginal characters, I need to be aware of the complexities involved in speaking for and about their experiences.

Many Indigenous people still feel resentment and anger about our colonial past and the inability of whites to understand the circumstances that created the present situation. Aboriginal people are also angry about the way they have been portrayed in white literature. Jackie Huggins contends that much of what non-Indigenous people have written about the Aboriginal people “has been patronising, misconstrued, pre-conceived and abused.”

The majority of representations of the Australian Aboriginal people in literature before 1788 were for the most part negative. The original inhabitants of this continent were described as “the miserablest People in the World” by William Dampier, and as “naked, treacherous, and armed with Lances, but extremely cowardly” by Sir Joseph Banks. When Cook wrote about Australia in the 18th century, he said the Aboriginal people were uncivilised, thus paving the way for terra nullius and possession. They were further stereotyped by the early Sydney newspapers which ridiculed the so-called “civilised” Aboriginal people, thus creating the stereotype of the “‘ignoble savage’: an ugly, comic figure whose image persisted well into the twentieth century.”

Australian colonial texts were dominated by a “discourse of savagery,” Clare Bradford argues, which situated the Aboriginal people “on the very border between men and animals.” On the other hand, stories that explore the violence and displacement suffered by the Aboriginal people as a consequence of settlement, “call into question the legitimacy of Australia’s foundation and undermine notions of progress and growth, and they thus constitute a threat to colonial discourse.”

Larissa Behrendt argues that frontier narratives are “colonial constructions” that can promote a false image of settler interactions with the first people of Australia. She asserts that we must challenge the stereotypes embedded in the colonial mindset in order to combat its inherent prejudices in contemporary society and, in particular, the law. One such frontier narrative is Eliza Fraser’s story. Following the shipwreck of the Stirling Castle in 1836, Fraser became a cult figure after her rescue and supposedly factual account of her time spent with the Aboriginal people passed into folklore, the extremely negative images of the Aboriginal people planted firmly into

the subconscious of countless whites. The impact of these types of narrative on Australian society was significant because they created “a version of history, which constructed stereotypes of Aboriginal Australians that gave impetus for the development of government policies and then continued to create societal support for ‘civilising’ through assimilative and segregative policies.”

The Aboriginal voice is totally absent from these “captivity” narratives which are used as vindication for politicians to intervene and control Aboriginal people, because “they” are dangerous and pose a threat to “Empire.” The real story, according to Behrendt, is that Fraser was saved by the Butchulla women, as she would not have survived without their help. The silencing of the Aboriginal voice denies the positive role the Aboriginal people played on the frontier–that is, they worked hard for the white people in various roles and, most importantly, how the women helped with childbirth and childcare. Fraser’s narrative, and others like it–which are supposedly authentic accounts of the past–disempower Aboriginal women and deprive them of “authority, responsibility and independence, making misogyny a legacy of colonialism for Aboriginal women.”

Colonial folklore and the law perpetuate the dichotomy of them/us, empire/other, civilised/barbarians. In response, Behrendt constructs her own narrative based on the 1997 Report, Bringing Them Home: “captured by savages . . . suffered cruel abuse at the hands of the savages . . . treated like slaves . . . suffered a fate worse than death.” In this way, she shows that it was the Aboriginal people who suffered violence at the hands of the colonisers, not the other way around.

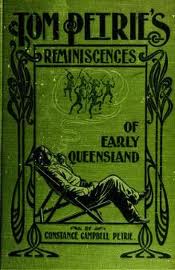

Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, though not a novel, is one example of a work written through “a sense of loss for traditional Indigenous lifestyles.” Walter Roth, Chief Protector of Aborigines, states in a letter to the editor included as a Note in Reminiscences that “the aborigines are fast dying out, and with them one of the most interesting phases in the history and development of man.” Constance Petrie was thus encouraged to record her father’s memories of the Aboriginal way of life before it was too late. In the mid-twentieth century, according to Margaret Merrilees, Australian novelists such as Eleanor Dark, Katherine Susannah Pritchard and Xavier Herbert were determined activists whose writing and political actions played a major role in bringing Aboriginal people into the drawing rooms of the white populace “at a time when few Aboriginal people had the resources, the language or the will to do so.” Contemporary Australians now have access to a wide range of writing by Aboriginal authors, beginning with David Unaipon’s Native Legends (1929) and continuing through the works of Oodgeroo Noonuccal to Kim Scott and Alexis Wright.

Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, though not a novel, is one example of a work written through “a sense of loss for traditional Indigenous lifestyles.” Walter Roth, Chief Protector of Aborigines, states in a letter to the editor included as a Note in Reminiscences that “the aborigines are fast dying out, and with them one of the most interesting phases in the history and development of man.” Constance Petrie was thus encouraged to record her father’s memories of the Aboriginal way of life before it was too late. In the mid-twentieth century, according to Margaret Merrilees, Australian novelists such as Eleanor Dark, Katherine Susannah Pritchard and Xavier Herbert were determined activists whose writing and political actions played a major role in bringing Aboriginal people into the drawing rooms of the white populace “at a time when few Aboriginal people had the resources, the language or the will to do so.” Contemporary Australians now have access to a wide range of writing by Aboriginal authors, beginning with David Unaipon’s Native Legends (1929) and continuing through the works of Oodgeroo Noonuccal to Kim Scott and Alexis Wright.

As a non-Indigenous writer I am aware that the Aboriginal people do not need me to tell their story and my decision to make those who inhabited the Brisbane area in the nineteenth century central figures in my novel is, as writer Margaret Merrilees puts it, “a conscious choice: a political choice, in the context of the times.” Moreover, I believe that a work that recounted Tom Petrie’s life without the Aboriginal people could in no way be an authentic rendering of the past.

In my opinion the interaction between the colonisers and the Aboriginal people is a shared heritage that can and should be explored by both black and white and that there are benefits for both sides in this process. Allan Robins argues that observing a culture from the outside can be beneficial and that representing Indigeneity from the exterior can promote understanding between cultures:

With due care, non-Indigenous representations of Indigeneity may prove useful, not only to the representer, but also to the represented: as Indigenous people become more aware of how they are perceived, and the changes that take place in those perceptions over time, they may become more able to formulate more and more effective understandings, responses and counter-representations of their own.

Positive representation of Aboriginal people by a white writer can lead non-Indige nous readers to the realisation that Indigenous people are not really that different from ourselves. According to Melissa Lucashenko, Nene Gare in her The Fringe Dwellers (1961), “had the imagination and the life experience to portray for a white audience—and maybe for the first time—a world in which Aboriginal men and women are both decent and normal, despite their being treated as far less than that.” This positive recognition of the “other” heightens understanding and is a step along the path to reconciliation.

nous readers to the realisation that Indigenous people are not really that different from ourselves. According to Melissa Lucashenko, Nene Gare in her The Fringe Dwellers (1961), “had the imagination and the life experience to portray for a white audience—and maybe for the first time—a world in which Aboriginal men and women are both decent and normal, despite their being treated as far less than that.” This positive recognition of the “other” heightens understanding and is a step along the path to reconciliation.

Young and Haley argue that, rather than harm Indigenous culture, writings by outsiders can benefit those cultures by stimulating interest and creating an audience for Indigenous literature. They further highlight the value of literature in inter-cultural understanding:

In the process of communication between cultures, literature has a vitally important moral role to play. It is through literature that readers undertake to imagine what it would be to be someone else, someone perhaps completely different, just as women can understand and imaginatively identify with a male character from the inside and vice versa, so can members of other cultural communities.

Stories written by a non-Aboriginal person about our common past thus represent an opportunity for discussion and the advancing of the reconciliation process. In order for contemporary Australians to move beyond the barriers of racism we need to look at our past relationships and recognise how they have shaped our present attitudes. According to Merrilees, “part of the way we unlearn our white racism is by telling stories, as honestly as we can—our stories of what’s happened, the interactions between races in this country.” It is this knowledge of where we came from, who our ancestors were and what they did that can lead us to greater tolerance and compassion for those who are different to ourselves. And these stories, especially if they are told by someone who has experienced Indigenous cultures, are important for all Australians. However, the way we tell these stories is critical to the way they are received by Indigenous and non-Indigenous readers alike.

References

Behrendt, Larissa. “The Eliza Fraser Captivity Narrative: A Tale of the Frontier, Femininity, and the Legitimazation of Colonial Law.” Saskatchewan Law Review 63 (2000): 145-84.

Borghino, José. “Rumbles in the Zeitgeist.” Australian Book Review 256 (2003): 46-47.

Bradford, Clare. Reading Race: Aboriginality in Australian Children’s Literature. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne UP, 2001.

Huggins, Jackie. “Respect V Political Correctness.” Australian Author 26.3 (1994): 12-13.

Lucashenko, Melissa. “Introduction: Fighting in the Margins.” The Fringe Dwellers. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2012.

Merrilees, Margaret. “Tiptoeing through the Spinifex: White Representations of Aboriginal Characters.” Dotlit 6.1 (2007): 1-14. 8 May 2012 <dotlit.qut.edu.au>.

Petrie, Constance Campbell. Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland. St Lucia, Qld: U of Queensland P, 1992.

Robins, Allan. “Representing Indigeneity: A Reflection on Motivation and Issues.” TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses. 12.1. April (2008). 17 August 2010 <textjournal.com.au >.

Young, O. James and Susan Haley. “‘Nothing Comes from Nowhere’: Reflections on Cultural Appropriation as the Representation of Other Cultures.” The Ethics of Cultural Appropriation. Ed. Young, O. James and Conrad G. Brunk: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Print.