What follows is a short section that I deleted from Turrwan in a bid to push the story along and not be distracted by too much historical detail. The passage is recounted by Tom Petrie.

“There are sixty licensed hotels and over a hundred illicit grog sellers in Sydney town, it’s outrageous!” Lang had once preached to my father. “It is our moral duty to stem the tide of debauchery that plagues the colonies,” he proclaimed. I met him  often when I was older and I can imagine the stiff back, the chest puffed out, head held high, hands grasping the lapels of his vest. He had a strong yet gentle face, the slightly pointed nose adorned with steel-rimmed spectacles that seemed to magnify his implacable gaze. His brown hair had receded from the expanse of his forehead, and though short, was surprisingly unruly for such a dapper man. Frail-looking sideburns dived behind the stiff white collar of his shirt, framing cherubic lips and a stubborn chin.

often when I was older and I can imagine the stiff back, the chest puffed out, head held high, hands grasping the lapels of his vest. He had a strong yet gentle face, the slightly pointed nose adorned with steel-rimmed spectacles that seemed to magnify his implacable gaze. His brown hair had receded from the expanse of his forehead, and though short, was surprisingly unruly for such a dapper man. Frail-looking sideburns dived behind the stiff white collar of his shirt, framing cherubic lips and a stubborn chin.

Lang had ensured that conditions on board the Stirling Castle were of a much higher standard than was generally the case for the long journey to the antipodes. Hygiene was important, so was instruction. Throughout the five months of the voyage, Lang’s four assistants, all clergymen, organised the men into classes that covered mathematics, economy and self-improvement, while assuring religious instruction and prayer on the Sabbath. As a measure of the men’s commitment to Lang’s strict moral principles, many of them, father included, signed a pledge of temperance.

The other guests were Lang, Wilhelmina, who was a devout Presbyterian missionary and would marry Lang when they later stopped over at the Cape; at this stage, the Reverend was still wooing her. Beside Lang sat his master builder George Ferguson and his wife Margaret.

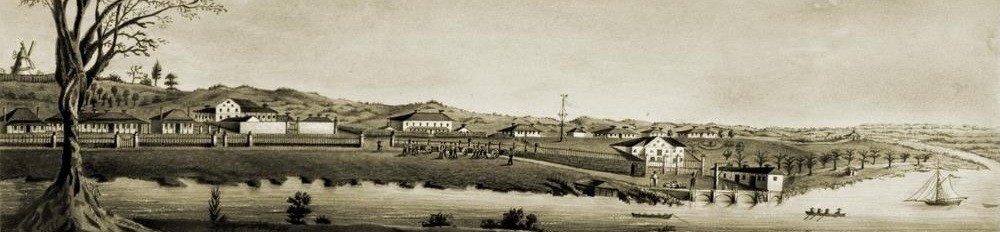

The Reverend Lang had arrived in Sydney in 1824 and built the Scots Church in the notorious Rocks area, whose narrow, dusty, ill-lit streets were infested with the worst kind of characters who would slit your throat for a penny. Lang certainly didn’t lack courage or conviction and would need these qualities to face the controversy he stirred with the construction of his college.

Before that though, in October 1831 when the Stirling Castle docked in Sydney Harbour, the emigrants were greeted with enthusiasm by the press, with the Sydney Gazette claiming it was “the most important importation the colony has ever received.”

Lang’s project came under criticism from emancipists, mostly of Irish and English descent; they had little in common with the skilled Scottish craftsmen who were much better educated than the majority of Sydney’s citizens and regarded themselves somewhat further up the social ladder than the ex-convicts and their descendants. The emancipists wanted to build their own college but couldn’t get funds or labour from the government and were therefore jealous of Lang. Groups of surly locals often sneered and even spat at the men from the Stirling Castle as they walked from their homes to work on the college. Father remembered one day when one loud-mouth had shouted: “There go those bloody emigrants who have come out to take the country from us.” It could not have been easy for my father whose humanitarian instincts would have perhaps sympathised with the plight of those who had lost their jobs to the Scottish contingent.

Click Lang for more.